Disclaimer: Just to be clear, I am not a financial advisor. Everything I've written above is just my personal understanding and perspective on the topic. It is not financial advice, and you should not treat it as a recommendation to buy, sell, or hold any asset.

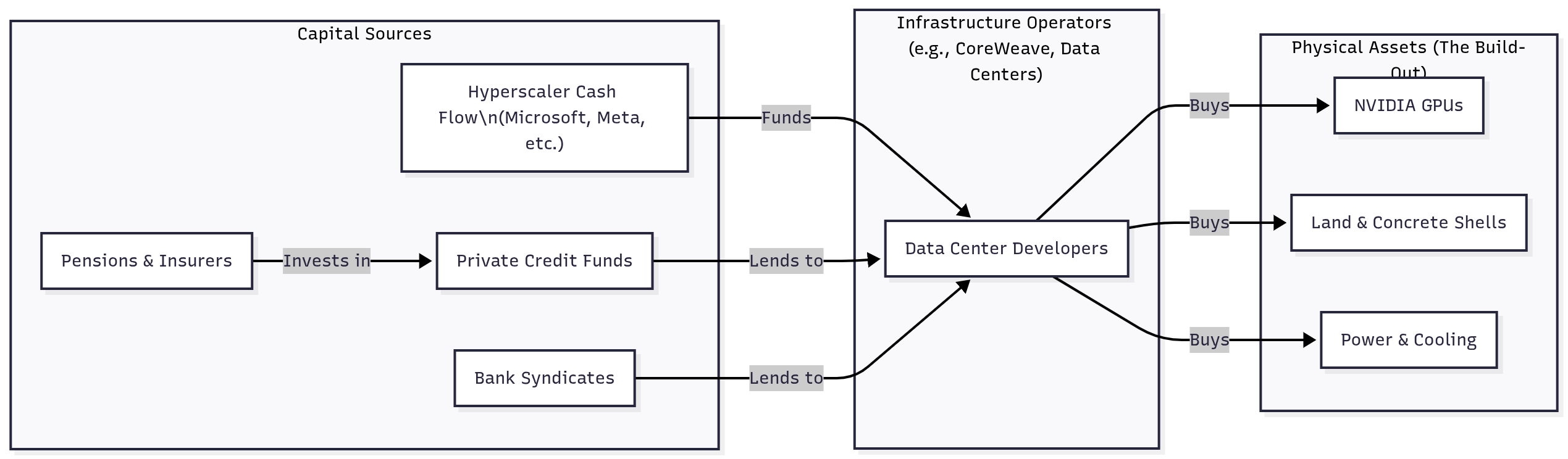

Most investors are not betting on “AI companies.” They are underwriting an infrastructure build-out with identifiable assets, contracts, and near-term cash flows. The actors, instruments, and incentives differ across the stack. So, the market can look frothy at the edge while the core is financed like a utility project.

1) The capital map

Independent estimates now cluster around multi-trillion-dollar outlays for data centers, power, and compute through the late 2020s. One widely cited view pegs cumulative data-center spend near $3T by 2028, with roughly $1.4T met by hyperscaler cash flows i.e., the big platforms paying for much of the build from operating cash.

The largest platforms have the balance sheets to do this. Microsoft disclosed $94.6B in cash, cash equivalents and short-term investments as of June 30, 2025. Meta reported $47.1B on June 30, 2025. Both continue to lift capex to expand AI capacity.

Recent announcements also show the political economy scale of this build. Meta has pledged $600B of U.S. investment focused on AI data-center infrastructure over the next few years. Whatever one’s stance on the framing, the message is clear: hyperscaler capex is intended to remain high.

2) Who supplies the rest of the money: private credit, banks, and securitization

The gap between hyperscaler cash and total need is being filled by private credit and bank syndicates, often in asset-backed, senior-secured structures. UBS and others flag private credit’s expanding role in AI data-center lending, with volumes rising rapidly through 2024–2025. At the same time, banks are partnering with private-credit managers to originate and distribute these loans.

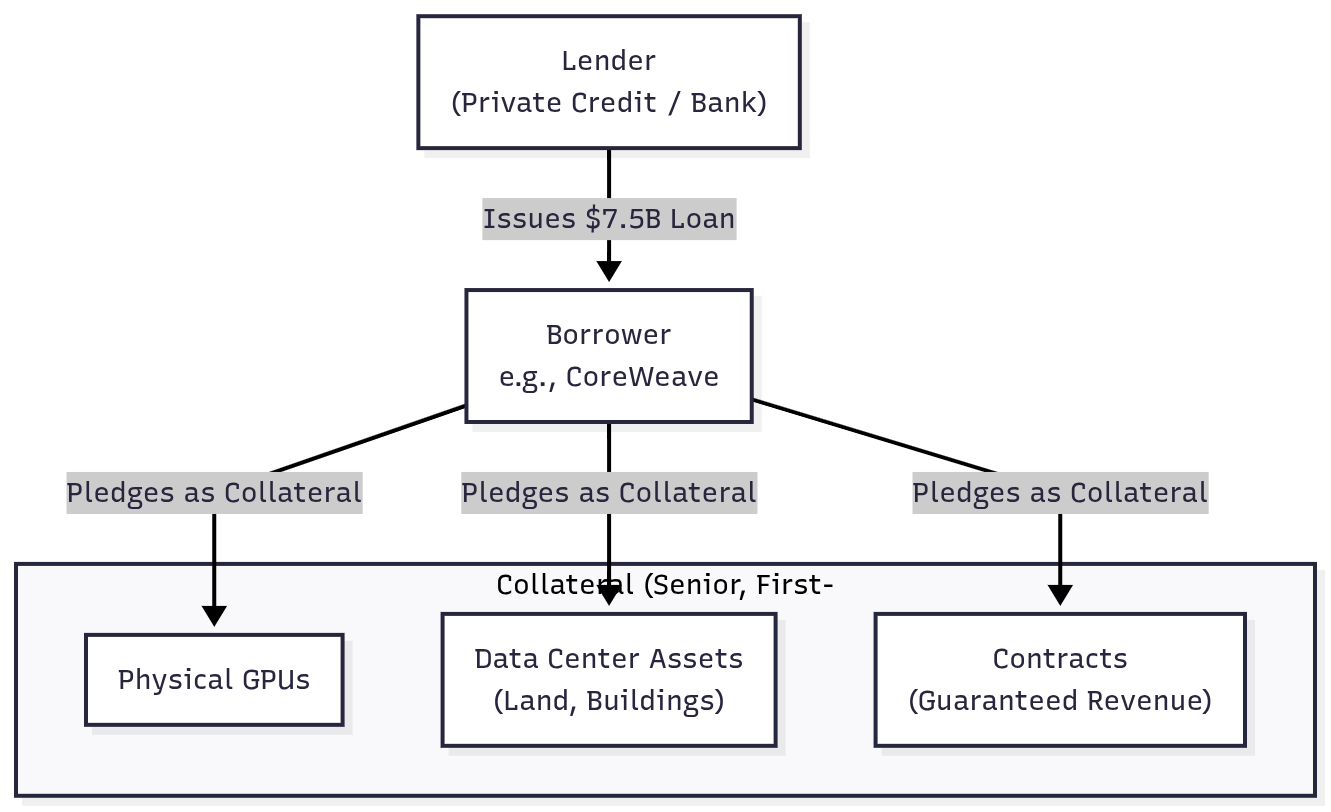

A concrete example: CoreWeave. In May 2024, it secured a $7.5B private-credit facility led by Blackstone and Magnetar to expand GPU data centers. In October 2024, it added a $650M revolving credit facility led by major banks. These are classic project-style financings: first-lien claims on equipment and data-center assets, sized to committed demand.

The financing chain then extends outward. Private-credit portfolios are increasingly syndicated or securitized (e.g., private-credit CLOs) and are also showing up in vehicles aimed at insurers and, at the margin, retail. That transmission path fund finance lines from banks, insurer allocations, and securitizations helps explain why capital is abundant for “picks-and-shovels” AI spending.

3) Why investors accept “depreciating assets”

GPUs age fast and refresh cycles are shortening. That raises obsolescence and depreciation risk for the compute fleet. Analysts picked up that risk explicitly in CoreWeave’s IPO coverage, and executives at chip vendors have acknowledged how new architectures reset asset lives. Lenders compensate by staying senior, taking collateral, and underwriting against contracted cash flows rather than speculative terminal values.

On the real-estate and power side, lenders can underwrite shells, land, interconnects, transformers, and long-lead thermal systems with conservative loan-to-cost / loan-to-value and step-in rights. 2025 is a record year for data-center development financing, with structures commonly in the 65–80% loan-to-cost range. This is familiar territory for private credit and infrastructure desks.

Asset-based finance is the point. Senior, secured paper on tangible assets plus contracted offtake can produce steady coupons for a few years regardless of which application startups ultimately succeed.

4) “Money goes in circles”: related-party demand and vendor finance

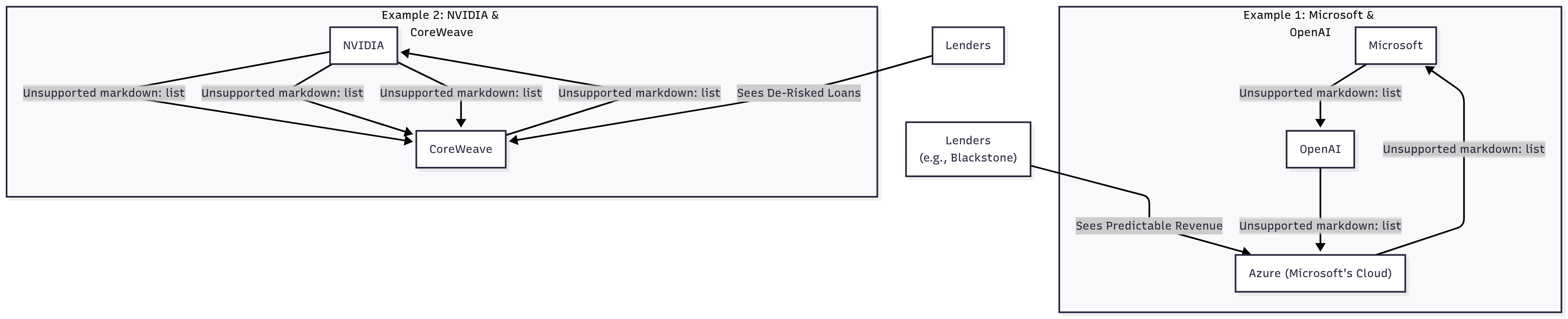

There is circularity, but it is mostly industrial contracting, not simple multiple-inflation. Examples:

- Microsoft invests heavily in AI and also sells capacity. OpenAI has contracted to buy an additional $250B of Azure services, a commitment that anchors future revenue for Microsoft’s cloud.

- CoreWeave signs multi-year, multi-billion compute supply contracts (e.g., OpenAI), while NVIDIA both supplies hardware and owns >5% of CoreWeave. NVIDIA also agreed to a structure that backstops CoreWeave’s unused capacity, aligning incentives across the stack.

These ties can concentrate risk and elevate valuations, but they also reduce cash-flow uncertainty for lenders who finance the underlying capacity. In other words, circularity makes the near-term income statement more predictable even as it can make the long-term equity value harder to judge.

5) Where the risk really sits

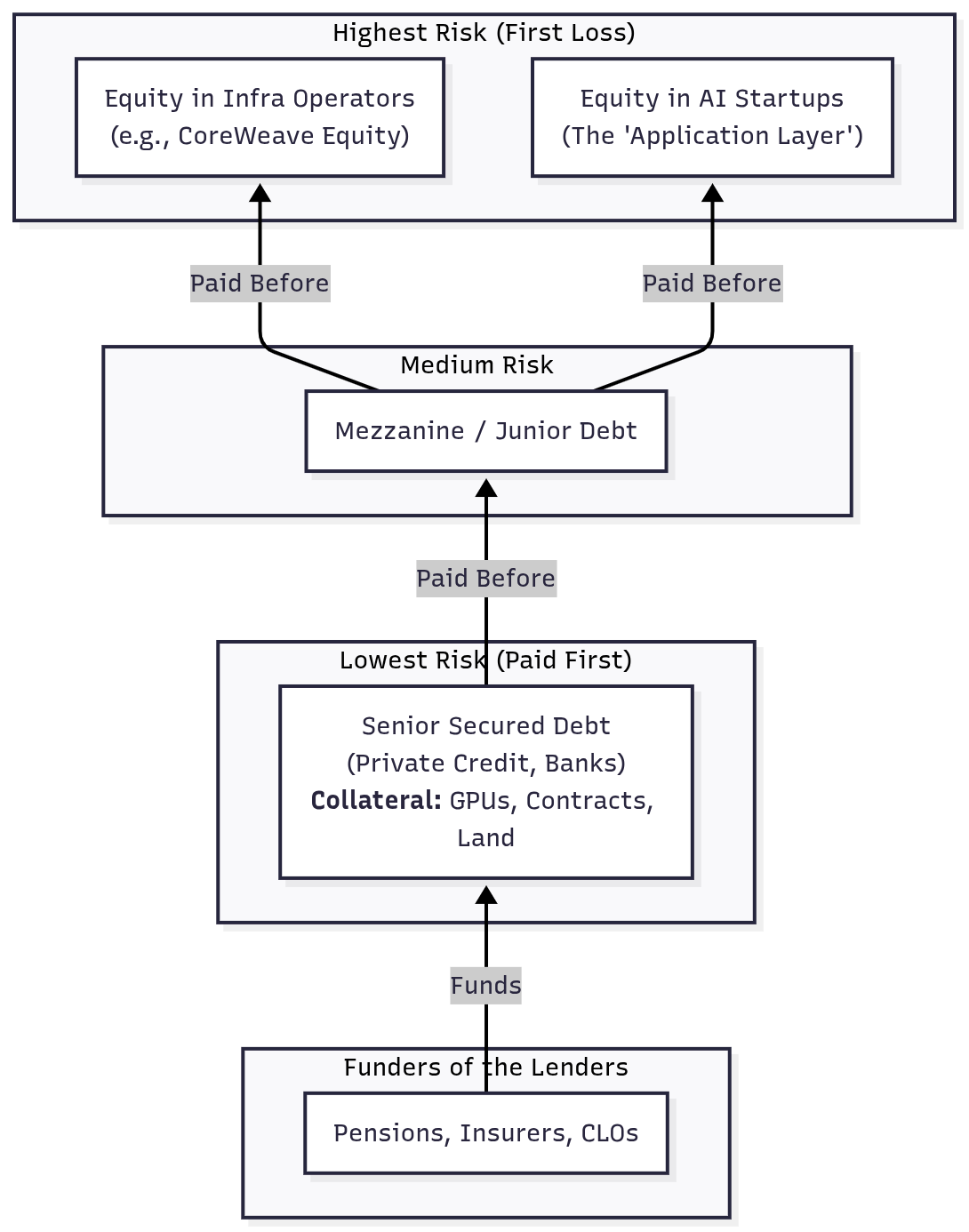

Loss absorption follows the capital stack:

- First loss sits with equity in infrastructure operators and application startups.

- Then with mezzanine and junior secured lenders.

- Senior secured private-credit lenders have collateral and covenants; they are paid before equity sees recovery.

- Who funds the lenders? Mostly pensions and insurers; banks provide subscription/NAV lines and buy structured exposure; retail is arriving through multi-asset funds and ETFs. That is the real transmission channel from “AI infra” to household savings not deposits directly funding GPU farms.

Banks do have growing exposure to private-credit managers and loans, which creates indirect links to the banking system. That is a prudential question supervisors are already tracking.

6) “But aren’t most AI startups unprofitable?”

Early-stage returns follow power-law dynamics in any cycle. Enterprise data is mixed: a minority of firms report company-level EBIT impact from AI today even as use-case benefits accumulate; funding flows remain high and concentrated. That combination heavy infra capex, concentrated demand, uneven productivity impact is consistent with an infrastructure-led build-out rather than a broad, cash-generating software wave.

7) Putting the mechanics together

- Why high-level investors keep investing: because they are financing assets + contracts with seniority and collateral, not promises of generalized AI prosperity.

- Why it looks like a bubble online: because equity valuations of application vendors, cross-holdings, and revenue pre-buys can look circular and concentrated.

- What could go wrong: utilization shortfalls, power/permit delays, or faster-than-modeled depreciation could impair equity and junior tranches; concentrated counterparties could transmit stress through the vendor-finance chain.

- What could go right: contracted capacity gets consumed, refinancing windows stay open, and assets amortize through cash flows before obsolescence catches up.

It is less a spectacle than a coordinated conversion of cash into chips, concrete, and megawatts underwritten by contracts and senior claims. The system will reveal its true efficiency only after a few asset-life cycles when the first big GPU cohorts roll fully off depreciation and the next contracts are priced on observed, not imagined, load.

Sources & further reading: CoreWeave private-credit facility and bank revolver; UBS/Reuters on private credit in AI; JLL on development financing; Microsoft/Meta cash and capex; OpenAI–Azure commitments; NVIDIA–CoreWeave cross-links; Morgan Stanley/Morgan-Stanley-cited estimates of total spend; Stanford/McKinsey on enterprise impact.